In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Science fiction is noted for the amazing diversity of its alien beings. More than a few of them are scary, or cruel, or heartless…not the type of creatures you would want to meet in a dark alley or forest. Those nasty ones definitely outnumber cute and friendly aliens. But one alien race, the Fuzzies, stands out for its excessive cuteness—an element that could easily overwhelm any tale including them. Rather than wallowing in cuteness, however, H. Beam Piper’s classic book Little Fuzzy turns out to be quite a tough tale about corporate greed and the power of people brave enough to stand against it.

I must admit right up front that H. Beam Piper is among my favorite authors of all time. It may be the result of encountering him in my early teens, that period when you tend to imprint on a good author the way a duckling imprints on its mother. Or it may be the way his outlook and political views (which I don’t always agree with) remind me of my dad’s. Or it might be the admirable competence and toughness of his protagonists. In any event, Piper wrote compelling stories with lots of adventure in good, clean prose that went down easy as a Coke on a hot day. And in Little Fuzzy, he was at his best. At the heart of the story is a courtroom drama that cleverly speculates about the impact that reliable lie detectors could have on jurisprudence. The characters are compelling and realistic, the depiction of the tiny aliens makes you wish you could meet them in real life, and the action never flags.

About the Author

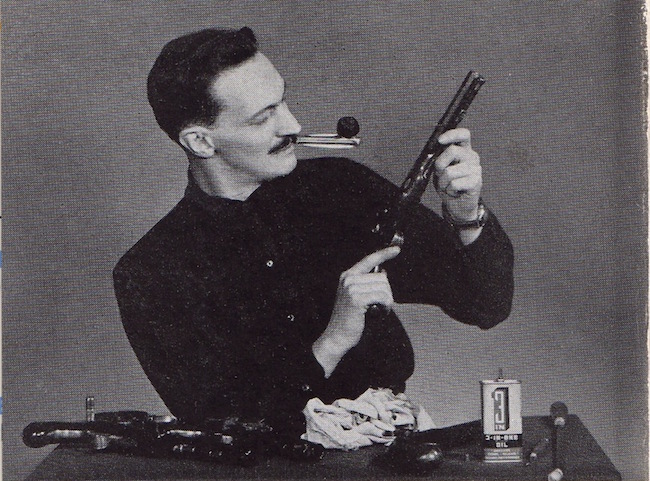

H. Beam Piper (1904-1964) had a short but consequential career in science fiction. Largely self-educated, Piper lacked higher education, but I suspect that his work for the Pennsylvania Railroad as a night watchman gave him plenty of time for reading, as he had a broad knowledge of many subjects. He had a keen mind, and his stories often included a clever twist, not obvious in advance, which makes perfect sense once it is revealed to the reader. His protagonists are intelligent and self-reliant, the type of people who can shape history.

He was a favorite of Astounding Science Fiction editor John Campbell and the readers of that magazine. In fact, if you had to pick an author whose work best fit the house style, Piper would likely be one of the first who comes to mind. Almost all of his fiction fits into a complex and detailed future history rivaling that of any contemporary. His career was tragically cut short by suicide just as he was hitting his stride as an author.

The Terro-Human Future History

During his career, Piper created two major series that, between them, comprise most of his published work. The first was the Paratime series, which included the adventures of Lord Kalvan, a Pennsylvania State Trooper inadvertently drawn into a parallel timeline (see my review here). The second was the sprawling Terro-Future History (which might be considered a subset of the Paratime series, if you accept the premise that the Terro-Future History represents one of the many parallel timelines where the ability to travel between them has simply not been discovered yet).

Piper’s Terro-Human history begins with an atomic war that obliterates most of the Northern Hemisphere, with nations in South America, Africa, and Australia surviving to establish the First Federation, an event which may not have seemed very far-fetched by readers in the early ‘60s. The future history shows the influence of academics like Arnold Toynbee, who looked for patterns in the rise and fall of civilizations over the grand sweep of history. As outlined in John Carr’s introduction to the anthology Federation, the First Federation was followed by a parade of governments and events, encompassing thousands of years of history, and including the “…Second Federation, the Systems States Alliance, the Interstellar Wars, the Neo-Barbarian Age, the Sword-World Conquests, the formation of the League of Civilized Worlds, the Mardukan Empire, [and] the First, Second, Third and Fourth Galactic Empires…”

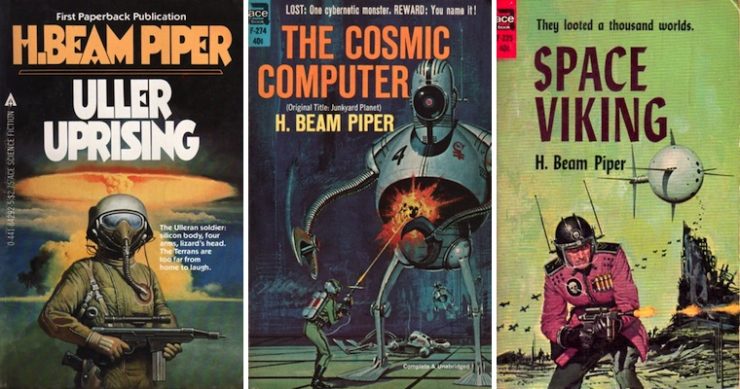

Piper’s tales in the Terro-Human series include the award-winning story “Omnilingual,” a tale of archaeology on Mars featuring a female protagonist (notable for the time when it was written; Jo Walton discusses it here). The Fuzzy books are also part of the series, which includes the novel Uller Uprising (sometimes written as Ullr Uprising), a gripping and morally complex tale of survival based on the Sepoy Revolt against British rule in India. The novel The Cosmic Computer (originally published as Junkyard Planet), set on a formerly strategic planet that’s become a backwater, follows the search for a powerful military computer that might hold the secret to saving an entire civilization. One of Piper’s most famous works, Space Viking, is a swashbuckling tale of vengeance set in a time when interstellar government has collapsed (he admired Raphael Sabatini, and to my eyes, here those influences are seen most strongly).

More Fuzzies

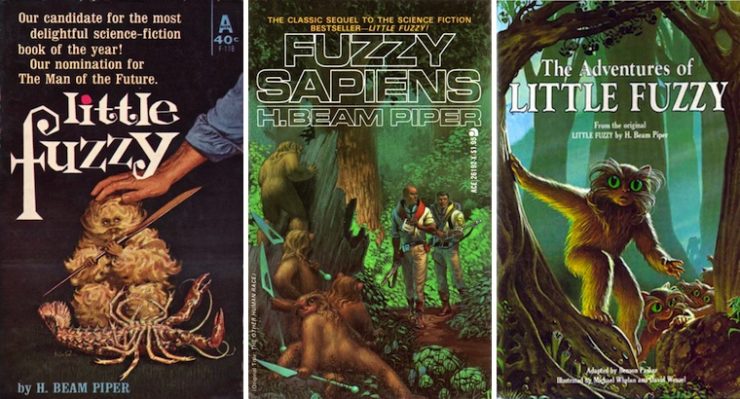

The first book in the Fuzzy series, Little Fuzzy, was published by Avon Books in 1962. Its sequel, The Other Human Race, was published by Avon in 1964. In the mid-1970s, Ace Books set out to reprint the entire H. Beam Piper catalog, with new covers by a promising young artist named Michael Whelan, which proved to be a commercial success, bringing sales not seen in Piper’s lifetime. Little Fuzzy and The Other Human Race were reissued in 1976, with the second book retitled Fuzzy Sapiens. It was rumored that Piper had completed a third Fuzzy book before his death, but the manuscript remained lost for almost two decades.

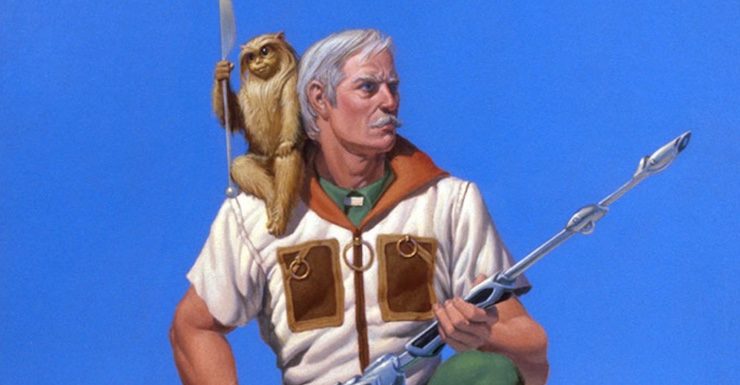

Ace arranged to have other authors continue the Fuzzy series, and two more books appeared; Fuzzy Bones by William Tuning in 1981, and Golden Dream: A Fuzzy Odyssey by Ardath Mayhar in 1982. Then, probably due to the popularity of Michael Whelan’s cute and big-eyed depictions of the Fuzzies, a children’s Fuzzy book appeared in 1983, The Adventures of Little Fuzzy, by Benson Parker, with a cover and endpapers from Michael Whelan and interior illustrations from David Wenzel (this book proved to be a bedtime favorite for my son). The Fuzzy illustrations, as well as other impressive work, helped Whelan gain significant attention within the SF community and launch a career that has included receipt of 15 Hugo Awards to date (see more of his work here). Then, in 1984, Piper’s lost Fuzzy manuscript was recovered, and Ace issued Fuzzies and Other People, the third book in the trilogy. Ace also issued an omnibus edition of all three of Piper’s Fuzzy books (and you can read a Jo Walton review of the three books here).

More recently, in 2011, author John Scalzi, a fan of the original books, decided to retell the story as a private project and writing exercise, He wrote a book, Fuzzy Nation, that was the literary equivalent of a movie remake. He got rid of anachronisms like Pappy Jack’s taste for chain smoking and highball cocktails, and gave the revised character the trademark Scalzi sardonic narrative voice. While it was not his original intent to publish the work, Scalzi was able to gain approval from the Piper estate to release the finished novel.

Another author who has continued the tales of the Fuzzies and written and published several other books based on Piper’s characters is my friend John F. Carr, an editor of the Ace reprints from the 1970s. He has also penned two biographies of Piper (you can find his Piper-related work listed here).

Little Fuzzy

Jack Holloway is a crusty old prospector searching for sunstones, a gem found in fossilized jellyfish on Beta Continent of the planet Zarathustra. He has leased a stake from the Zarathustra Corporation, and pursues his goal using rather destructive means: by blasting rock, and then moving the rubble with a flying contragravity manipulator. His luck has recently taken a good turn with the discovery of a deposit rich in sunstones, but he is vexed by an infestation of land prawns, the result of unusually dry weather.

The Zarathustra Corporation has a Class-III charter from the Terran Federation that gives them a chokehold on the planet, which they have further augmented by bribing Federation Resident General Nick Emmert. Their employees, led by Victor Grego, are doing their best to maximize their profit. They have recently drained massive swamps on Beta Continent for cropland, ignoring the fact that this is causing droughts downwind. The company’s Director of Scientific Study and Research, Leonard Kellog, is not concerned, as the profits they will generate are too impressive to ignore. Among those working for Kellog are mammalogist Juan Jimenez, xeno-naturalist Gerd van Reebeck, and psychologist Ruth Ortheris.

Jack comes home to his cabin one evening to find a creature visiting: a small, furry biped that he immediately nicknames Little Fuzzy. He finds the creature to be friendly and intelligent, learns that it likes a field ration called Extee Three, and sees it use a borrowed chisel to kill and devour one of the pesky land prawns. Jack, who hadn’t realized how lonely his life had become, adopts Little Fuzzy into his household, and is delighted when the creature brings a whole family of Fuzzies home, including Baby Fuzzy, who likes to sit on top of people’s heads. Jack shows them to local constables Lunt and Chadra, who are also captivated by the creatures. He also sends a message to his friend, Dr. Bennett Rainsford, a naturalist with the independent Institute of Xeno-Science. Rainsford is excited by what he sees, immediately deciding that the Fuzzies are sapient beings, and sends off reports to Jimenez and van Reebeck. It appears the Fuzzies have migrated into new territory to follow the land prawn infestation. When word reaches Kellog and Grego, they are horrified. If these creatures are indeed sapient, it would cause the Federation to reclassify Zarathustra as a Class-IV planet, invalidating the company’s charter, and resulting in its replacement by a far less lucrative agreement. They need to have the Fuzzies identified as a non-sapient species, and are willing to take any steps necessary, no matter how ruthless, to make that happen.

On the moon Xerxes, Commodore Alex Napier of the Federation Space Navy is monitoring these developments. He has agents on the planet who are keeping him informed. He doesn’t approve of the Zarathustra Company and their methods, but is prevented from interfering with civil affairs in anything but the direst of circumstances.

Kellog, Jimenez, van Reebeck, Ortheris, and an assistant named Kurt Borch immediately fly out and set up camp near Jack’s cabin. Kellog becomes increasingly angry, as the intelligence of the Fuzzies is clear to everyone who meets them. Jack sees what Kellog is up to, and when van Reebeck quits the company in disgust, Jack offers to partner with him as a prospector. Jack decides to kick the company team off his land, and calls the constables to help evict them. When one of the female Fuzzies, Goldilocks, tries to get Kellog’s attention, Kellog kicks her to death in a fit of rage. Jack immediately attacks him, punching him mercilessly, and Borch pulls a gun on him. Jack is an old hand with a pistol, and kills Borch in self-defense. When the constables arrive, Kellog accuses Jack of murdering Borch, and Jack in turn accuses Kellog of murdering Goldilocks, identifying her as a sapient being. This sets things in motion for a trial that will not only decide the charges of murder, but will also put the company charter into question.

At this point, the book becomes a well-plotted courtroom procedural with lots of twists and turns, which I will not discuss in detail to avoid spoiling the fun for those who have not read it. Much of the drama comes from the disappearance of Little Fuzzy and his family during the proceedings. As I mentioned earlier, the book cleverly examines the impact a reliable lie detector (the veridicator) would have on police methods and trial procedures. The character development from the first portion of the tale comes into play as the plot brings the various characters into conflict. While Ruth Ortheris is outnumbered by the many male characters, they are foolish to overlook her, as she ends up playing a pivotal role in the proceedings. And if you aren’t a fan of the Fuzzies by the end of the book, you’re in a distinct minority, as I’ve never met anyone who wasn’t captivated by them.

Final Thoughts

Little Fuzzy is a good book from start to finish. The sheer cuteness of the Fuzzies and the greed of the various Zarathustra Corporation officials offer readers the perfect balance of sweet and sour. The characters, as they are in many books of the era, are overwhelmingly male, and some of the behaviors are anachronistic, but I would not hesitate to recommend the work for any reader, young or old. Moreover, the various ethical questions the book poses can generate some good, thoughtful discussion with a younger reader.

Many of Piper’s early works have gone out of copyright into the public domain, and can be found free of charge on the internet via sites like Project Gutenberg. So if you are interested, you don’t have to look far for them.

And now it’s time for you to share your thoughts: What did you think of Little Fuzzy, or Piper’s other tales from the Terro-Human Future History? Do you share my affection for the author and his works?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.